From a clinic population of close to 850 patients with keratoconus, Dr. Koppen selected patients with extremely severe KC for her study. She would offer the patients scleral lenses to see if they could achieve useful vision and avoid transplant surgery. To identify these patients, she used a Scheimpflug tomography to measure the corneal curvature (maximal keratometry or max K): the higher the K reading, the more severe the astigmatism. While each doctor has their own range of how they classify KC, for general purposes, normal eyes, or those with very mild keratoconus will have a K reading below 45 diopters; moderate KC is usually defined as the range between 46 and 52; and severe or advanced keratoconus are K readings above 52 diopters. The patients she she enrolled in her study all had K reading ≥ 70. By all accounts, these eyes would be defined as advanced or extreme cases of keratoconus.

Of the 51 eyes she followed through her five-year study, 40 were successfully treated with long term scleral lenswear and 9 eyes had undergone corneal transplant surgery: 5 because contact lenses did not provide adequate improvement of vision, 2 were intolerant of the scleral lenses, 1 eye developed hydrops, and 1 patient was unable to manipulate the scleral lens. (There were additional patients who were eligible for the study but did not enroll, and patients who enrolled and dropped out mid-study.)

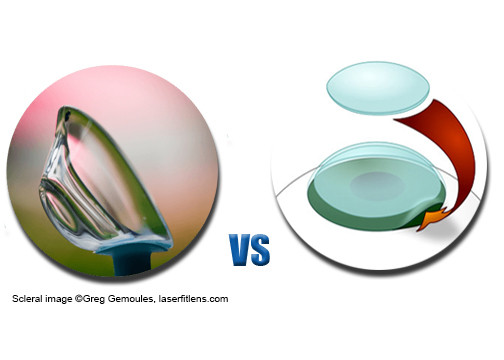

Dr. Koppen concluded that these 40 eyes with extreme KC would have likely undergone transplant surgery had scleral lenses not been available. She stresses that a “major advantage of scleral lenses vs. keratoplasty (corneal transplant) is its total reversibility. If the patient does not find the lens proves good visual acuity and high quality of life, lens wear can be abandoned and surgery performed.”

At an international meeting of contact lens experts, Dr. Carina Koppen, MD, PhD (left) of Belgium discussed her research and a recent paper published in the American Journal of Ophthalmology (1).

At an international meeting of contact lens experts, Dr. Carina Koppen, MD, PhD (left) of Belgium discussed her research and a recent paper published in the American Journal of Ophthalmology (1).