Acute Corneal Hydrops: A serious complication of KC

New Scleral Lens Product

January 6, 2022

Common KC Mistakes to Avoid

January 28, 2022Originally published in NKCF Update (August 2020).

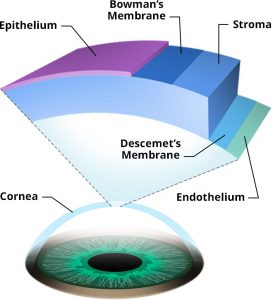

Acute corneal hydrops happens in less than 3% of all individuals with keratoconus (KC), but it is a serious, vision threatening complication. Acute corneal hydrops occurs when there is a sudden break in the innermost portion of the cornea and aqueous fluid pushes forward. The break is considered spontaneous, but some patients recall prior to the event, they had been rubbing their eyes, or experienced a powerful sneeze or cough, or forceful nose blowing that may have temporarily increased pressure in the eye and caused a rip or tear in the endothelium and Descemet’s membrane (DM).

Patients who suffer an episode of acute corneal hydrops describe suddenly blurry vision and extreme light sensitivity. While some patients do not complain of pain, others say the pain associated with the event is intense. These symptoms can linger for several weeks.

The look of hydrops is unique. As fluid enters the stroma from the break in the DM, an opacity develops, often in the area of the cone or steepest part of the cornea. The fluid appears as a pale, whitish shape.

The treatment for hydrops is to wait for the break in the DM to reattach and for the fluid in the stroma to reabsorb. Dr. Tara McGeehe, MD, a corneal specialist from the University of Virginia Department of Ophthalmology has considerable experience treating patients who develop hydrops. “The traditional treatment is to allow the healing to take place on its own. I may prescribe eyedrops that will reduce pain and swelling and promote healing, but I wait for the DM to heal itself.”

Other doctors prefer to hurry the process along by introducing an air or gas bubble via an injection into the eye. The bubble pushes up against the DM, holding the tissue in place and closing off any leaks. While this treatment decreases the healing time, there are additional risks associated with this injection therapy and patients must hold their head a certain way (usually lying down) for a few weeks for the therapy to be effective.

Whichever method your doctor recommends, plan on several office visits during the healing period. Your doctor will want to closely monitor progress.

A significant problem during the 2-4 months it normally takes to recover from corneal hydrops is that, for many patients, contact lenses cannot be worn. A doctor may put a bandage contact lens over the eye in the beginning of treatment in order to quiet the eye, but may be reluctant for a patient to resume daily contact lens wear if there is a danger of causing additional trauma to the eye. For some individuals with hydrops, their eye is ‘out of service’ until it recovers.

Dr. McGeehe explains that a major concern she has with her patients who develop hydrops is the location and density of the resulting scar. As the fluid reabsorbs, a scar may develop where the cornea was stretched; regaining clear vision may be impossible, even with custom contact lenses. “By 2-3 months, I have a general sense if surgery is likely to be required for vision improvement, but so much healing can happen with time it is impossible to accurately predict in the first several weeks after hydrops develops whether surgery will be needed.”

She follows her patients closely, adding that she wants “to make sure symptoms are controlled: that corneal swelling (edema) is improving and that the top layer of the cornea (epithelium) is not getting swollen or breaking down as this can lead to an infection.”

McGeehe noted that, “We still have a lot to learn about hydrops, like why it happens in some individuals with keratoconus and not others.” She reports that those most likely to develop hydrops are those with a younger age of diagnosis, more severe keratoconus (i.e., a weaker or steeper cornea), and those with poorer vision or a history of eye rubbing. She noted that contact lens wear does not seem to increase the risk of developing hydrops. Dr. McGeehe urged patients who develop symptoms like sudden and extreme light sensitivity or eye pain to notify their doctor immediately.

Dr. Tara McGeehe, MD is an Assistant Professor at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. She completed her ophthalmology residency at the University of North Carolina and her fellowship in cornea disease and at the University of Iowa. Dr. McGeehe specializes in eye surgery and the care of complex cornea diseases including keratoconus.

Dr. Tara McGeehe, MD is an Assistant Professor at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. She completed her ophthalmology residency at the University of North Carolina and her fellowship in cornea disease and at the University of Iowa. Dr. McGeehe specializes in eye surgery and the care of complex cornea diseases including keratoconus.